You can hop in a potato-sack race, careen down a hay slide and enter the scarecrow-making contest at the seventh Bovina Farm Day, which will take place this Sunday, Sept. 6. At 2:30 p.m. there will be a talk about heirloom apples; at 4:30 p.m. cows will be milked. And all day long you can ogle goats and sheep, and peruse displays of maple syrup, meats, and cheeses produced on Bovina farms.

The annual event—a celebration of the town’s agricultural heritage and a showcase for local farms and producers—will be held on the dairy farm of Ed and Donna Weber, hosts of Bovina Farm Day every year since the Labor Day weekend tradition began in 2009.

But just as exciting as these and other activities—and who isn’t eager to sample the “Bovina Casserole,” to be concocted using only local ingredients?—is the fact that longtime locals and newcomers to the area are banding together to write a new chapter in farming in this smallest town in Delaware County.

Above: A newborn goat on Webcrest Farm learns to nurse, with some help from Donna Weber. Photo by Jane Margolies.

The old refrain is that farming is dying, with the number of dairy farms in Bovina’s 44 square miles down to three from a peak of well over 100 in the 19th and 20th centuries. But while it might be too soon to say that Bovina farming is booming, it’s certainly clear that it’s changing, with multi-generational dairying families branching into other types of farming, and retirees, career-switchers and energetic young couples starting up small-scale operations that produce everything from organic vegetables to cut flowers.

“Farms are diversifying,” said Evelyn Stewart-Barnhart, a Bovina native and founder of Farming Bovina, a grassroots organization that aims to preserve and support farms in the area. As of this year, the group is the sponsor of Bovina Farm Day.

Above: Donna Weber, one of the hosts of Bovina Farm Day, will be organizing hayrides this Sunday. Photo by Jane Margolies.

Although Bovina has long been linked to dairying, early farms were actually a varied lot, raising sheep and pigs, growing potatoes and grain, and producing maple sugar and honey.

In fact, although it’s widely believed that the town, which was carved out of Delhi, Middletown, and Stamford in 1820 and situated on the headwaters of the Little Delaware, was named in honor of its dairying (“bovine,” after all, is commonly associated with cows), the name actually may originally have been intended to evoke “a more generic term akin to ‘pastoral,’” according to Bovina historian Ray LaFever—a reference to the rolling, rocky land’s suitability for grazing.

By the 1890s, however, Bovina had around 120 dairy farms and was out-and-out famous for its butter, produced from the milk of Jersey cows and possibly served in the White House, according to LaFever.

In 1902 the Bovina Center Co-op Creamery opened, giving farmers a place to make their butter as well as other milk products. Donna Weber, who lived nearby as a child, recalls waking up to the “clanging” of metal containers as farmers brought their milk to the facility.

“It was the background noise of town,” she said.

Above: Cows of Webcrest Farm. Photo by Matthew Dell.

The closing of the creamery in 1973 contributed to a dramatic drop in dairying, though federal policies and competition from large Midwest farms also played a large part in the decline.

(Bovina is currently abuzz with reports that the creamery, which has most recently been used as an auction house, could soon revert to its original purpose, but the parties in contract to purchase the building say it is “too soon to talk,” since processing milk is not permitted there under present town zoning.)

But while the Webers’s Webcrest Farm, Pepacton Farm and LaurDom Holstein continue dairying, many long-time dairy farmers have shifted course. Jack and June Burns of Bramley Mountain Farm, for instance, 6th-generation farmers, now raise Belted Galloway beef, working with 7th- and 8th-generation members of the family.

Steve Burnett is one of the newer farmers in the area who haven’t inherited farms but are starting them from scratch. A former marketing design professional in New York City, Burnett bought a second home on Bramley Mountain Road in 1989, and a decade later he and his wife, Kristie, made a “life decision” to devote themselves full time to building an organic vegetable farm.

Above: The sign in front of the farmstand at Burnett Farms. Photo by Jane Margolies.

Over the years they’ve added parcels so that their Burnett Farms now spans 150 acres, and they’ve learned to coax tomatoes, squash and corn from the rocky soil, selling their produce at their cute farmstand on East Bramley Mountain Road. They have plans to expand into pigs and U-Pick raspberries.

Flower growers Irene Berkowitz and Matthew Dell, who started their Treadlight Farm in Bovina’s Crescent Valley just this year, are the newest farmers in town, cultivating delphiniums, sweet peas and other finicky and unusual varieties of cut flowers on a plot they rent overlooking the Webers’s 280-acre spread.

It wasn’t just the drop-dead beauty of the area that drew them to Bovina, but also the fact that in other counties within reach of New York City successful organic farms had already been established—and competition was growing at farmers markets.

“We got suspicious looks from farmers in other upstate counties, but we didn’t get that in Delaware County,” Dell said. “People were really excited about another organic farm starting up. Other farmers were really welcoming.”

Of course, starting up a farm is one thing; profiting from it, or even just breaking even, is quite another—a challenge experienced by farmers across Delaware County and, indeed, the entire watershed area, according to Rebecca Morgan, the executive director of the Oneonta-based Center for Agricultural Development & Entrepreneurship.

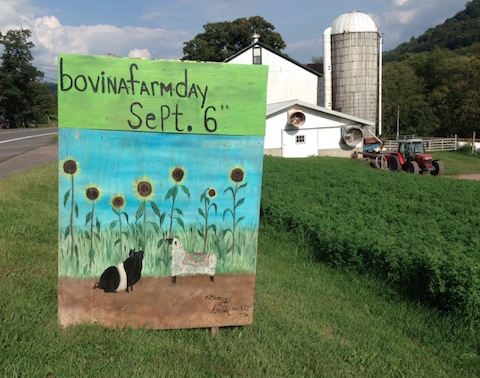

Above: A Farm Day sign painted by folk artist Nancy Kulikowski. Photo by Jane Margolies.

Farming Bovina, founded in 2012, aims to unite new and longtime farmers so that they can share information and advice and promote themselves as a group. The organization, with funding from Pure Catskills, produced a glossy “Farm Trail” brochure with a connect-the-dots map of farms to encourage people to buy locally.

Above: Farming Bovina's logo.

Joan Burns, who is on the board of Farming Bovina, was the driving force behind the group’s logo, which depicts a brawny straw-hatted farmer with a barn and silo emblazoned on his overalls. The group is experimenting with small, circular stickers printed with the logo that farmers can affix to their products as a way to brand Bovina’s bounty.

When the Weber and Stewart families, the originators of Bovina Farm Day, were looking for help planning, setting up and running the event this year—in the past, as many as 1,200 people have shown up—their fellow members of Farming Bovina stepped up to the plate. The group hopes that the event will help connect the farming community with the broader public.

And perhaps even persuade others to jump in.

“Ideally, we’d like to see a resurgence of farming, and we’d like to see this land used again,” said Steve Burnett, who is on the board of Farming Bovina. “I’d like to think that as more and more people come up here as visitors and second-home owners, there are those who will decide to take a swing at it.”

Bovina Farm Day. Sunday, Sept. 6, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Webcrest Farm, 648 Weber Road (off Crescent Valley Road), Bovina. farmingbovinany.org.