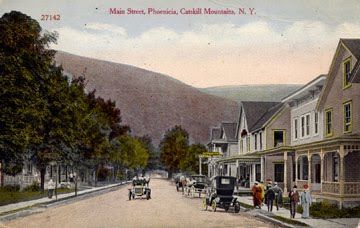

Above: Vintage postcard of Main Street, Phoenicia. From the collection of local resident Stephen Bernstein; shared by the Woodland Valley View blog.

Small towns have some big advantages. They also have serious drawbacks. I came for the advantages and deal with the drawbacks. Mostly it’s a fair exchange, but it does fluctuate.

Most people stick to what they know best, and that’s the kind of place where they grew up; big city, small city, suburb, village, wilderness. Some of us figure out fairly early that we need to be somewhere else. Others take longer to realize where they ought to be. And some of us seem to have little choice in the matter. Rightly or wrongly, we end up feeling stuck. The population of most places is a mixture of all of the above. That’s the case for Shandaken, though we have our own special blend; we're a bit richer in older urban expats and part-time refugees than is typical of small-town America.

The pace of life is slower in small towns. And incomes, for those who make them locally, tend to be lower than what can be earned in most cities for comparable work -- if there is comparable work at all. The job market remains thin in small towns; not so many jobs and not so many workers. An imbalance of some sort is usually the norm, with not enough of one or the other at any given time or place.

Small towns usually get left alone more than most other places. Some would say they get neglected. There's less intrusion, but also less support. Most people figure out how to get by with less when they live off the well-paved path. Some choose small-town life because getting by with less is a value they either adhere or aspire to. Some have cut back as far as they can already, and with further cuts looming on the horizon, they worry they won't be able to get by any longer.

People who grow up and remain in small towns get attuned to small-town living in ways that late arrivers often have trouble grasping. But being brought up in intimate familiarity with small-town life can leave one ill-suited to appreciate the allure that a fast-paced and competitive urban lifestyle might hold for others. Worlds can separate near neighbors in small towns, depending on where they come from, and how open they are to absorbing a differing world view.

Small towns make us face each other in ways that cities don’t, and there’s an irony to that. One is seldom away from others in a city, or crowded in a village, but crowds create a feeling of privacy that can't be found in a one-on-one encounter on a quiet village street. Familiarity breeds love, and it also breeds contempt. Both can coexist in small towns, where no one can be a stranger for long.

Most folks living in rural hamlets tend to be independent. When it comes to most anything, most of the time we're on our own, and we know it. There’s not a multitude of alternatives to turn to nearby for anything. But we're also interdependent on each other, in ways city people seldom are.

When it’s time for a local election it’s nearly impossible not to have personal feelings influence considerations. But they are oddly ineffective in deciding who should simply be avoided, since usually that can’t be managed. One can minimize contact with someone, but chances are you will need their help, or at least their tacit consent, for something sooner or later (likely sooner if they have some role in the local economy).

Small towns make us face each other in ways that cities don’t. They push us to accept each others' imperfections, and drive us crazy if we can’t. They make us appreciate what we have, and they remind us of what we lack. They teach us to get by with a little less, and sometimes they lull us into not seeking enough. I live in small-town America by choice. I came for the advantages and deal with the drawbacks. So far, I think it’s a good exchange. Ask me again next year.

Tom Rinaldo writes the Dispatches from Shandaken column for the Watershed Post's Shandaken page. Email Tom at tomrinaldo@watershedpost.com.